MOVIE NEWS

THE FLASH

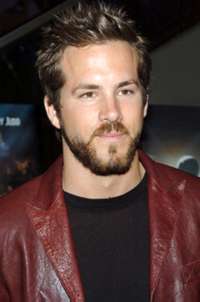

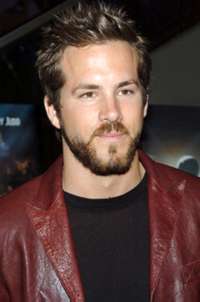

'FilmRoach' reports that Ryan Reynolds (Blade Trinity) is keen to take the

lead in any future movie based on comic-book hero The Flash.

Reynolds has apparently stated "I am the Flash" and hopes the screenwriter,

David Goyer, who worked with Reynolds on Blade, will push for Reynolds to

take the role of a chemistry student gains incredible speed after a freak

accident.

NATIONAL TREASURE 2

The first movie cost a massive $100 million to make, but despite average

reviewed it took $318 million at the worldwide box office, so now 'Walt

Disney Pictures' have agreed to a sequel.

Director Jon Turteltaub talked to 'CRIonline.com' and mentioned that the

sequel should be filmed in a romantic and mystical country, and China is on

the top of his list. He is now seeking a screenwriter to develop a script

for the second instalment.

X-MEN 3

Okay, so Britain's own Matthew Vaughn is in the director's chair, but which

X-Men are joining the team this time? Well, first up is fan-favourite The

Beast, then Gambit and Angel (who will be a woman).

THE RING 3

Director Hideo Nakata (The Ring 2) has told the 'Chicago Sun-Times' that he

doesn't rule out another instalment of the horror franchise, saying: "I

wouldn't be surprised if there was another one. I'd love to do Ring Three.

In Japan, I directed a Ring prequel called Ring Zero (right). It's about how the

little girl was killed at age 8."

In relates news, 'Moviehole' reports that Naomi Watts will not return for a

third Ring movie because 'DreamWorks' "will go off in a different direction

for the second sequel" - which could mean the prequel idea has credence.

STAR WARS: 3-D

At 'ShoWest' recently, directors George Lucas, James Cameron, Robert

Zemeckis and Robert Rodriguez gave a presentation on 3-D movies.

All four directors are pushing for a new-wave of 3-D entertainment to hit

cinemas in the next few years, starting with Cameron's upcoming Battle

Angela Alita.

Lucas himself presented the first 8-minutes of Star Wars Episode IV,

transferred in 3-D, before announcing that the original Star Wars trilogy

will be released in theatres with a new 3-D transfer for the saga's 30th

Anniversary - in 2007, 2008 and 2009.

SPIDER-MAN 3

Thomas Hayden Church (Sideways) has been approached to play a villain in

Spider-Man 3. Sources suggest this could be The Sandman, purely on the basis

that Church would be easier to imagine in that role.

In similar news, the 'New York Daily News' spoke to Chloλ Sevigny (American

Psycho, right) who said she's trying to get a role in Spider-Man 3.

Sevigny: "I'd love to be in Spider-Man 3! There's a villain in it who's a

blond, buxom girl, and I'm trying to get it! That [may] surprise people,

since actors are always thought of as their last film or who they were. I

think I'll always be drawn to films more difficult to watch, but I don't

want to be a snobby cinephile."

So who is this buxom character Sevigny mentions? Could it be Spider-Man

villainess Black Cat..?

WONDER WOMAN

The Hollywood trades have all reported that Joss Whedon (Buffy The Vampire

Slayer) will write and direct a Wonder Woman movie.

Whedon: "Wonder Woman is the most iconic female heroine of our time, but in

a way, no one has met her yet. What I love most about icons is finding out

what's behind them, exploring the price of their power."

"When [producer Joel Silver] and I began discussing the character, I

realized there is a woman behind the legend who is very fascinating, very

uncompromising and in her own way almost vulnerable. She's someone who

doesn't belong in this world, and since everyone I know feels that way about

themselves, the character clicked for me."

Whedon's movie Serenity, a movie spin-off from his cancelled TV series

Firefly, is due for release in September.

INTERVIEW - PAUL GREENGRASS, director (The Bourne Supremacy)

Terry Gilliam has been mentioned, it looked like Darren Aronofsky would take

the helm a year ago, but now British director Paul Greengrass is the man in

charge of (arguably) the greatest comic-book never filmed - Alan Moore's

fabulous superhero opus Watchmen...

'CHUD' have interviewed the director, who had this to say in the first two

parts of their three-part chat... go to

CHUD.com

for more in the coming weeks...

Q: You're working on [Watchmen] pre-production right now?

Greengrass: It's gearing up now. It's sort of about two months in now, about

six weeks in.

Q: What are you working on at the moment? Costumes and sets?

Greengrass:

It's a bit like how do you fit fifteen people through a small

door simultaneously. That's what pre-production is like in the early stages.

How do you fit an American football team through a door that's about two

feet wide and three foot tall. You have to crew up first of all not first

of all, these are in no order of priorities, these are just the things you

have to do. You have to start designing sets and wardrobe. You have to start

really analyzing how you're going to make the film. You have to start

working on the screenplay. You have to start thinking about casting. You

have to start thinking about budgets. We've made a good start.

It's interesting the kind of issues that first raise their head, really.

How do you deliver the Citizen Kane of comic books to screen? That is

basically the problem. It's a bit intimidating to be honest. I believe two

things, really: I do believe, obviously because I am here, that you can make

a film based on Watchmen the novel that is both truthful to the novel and

also works in two hours. I really do believe that, I wouldn't be here if I

didn't.

The second point is that I believe in an odd kind of way that it's twenty

years since Watchmen, give or take a year or two certainly twenty years

since it was set and I think in many ways a lot of what Watchmen was about

is very, very relevant to today.

I think that those are the two things that beat most passionately inside me.

Q: How did you first become aware of the novel, and how did you become involved with this project?

Greengrass:

I was going to say that the interesting thing from my point of

view I got a call in November or December, not that long ago, saying had I

heard of Watchmen and was I interested in doing a film. I said are you

kidding, of course I had heard of Watchmen. But the interesting thing from

my point of view is that I'm not a person steeped in comic book lore. That's

not where I come from. It wasn't something that I didn't sit as a child

and read millions and millions of comics.

I'm a Brit, as Alan Moore is, and Watchmen I read at the time that it came

out. The reason I read it is because at the time there was a lot of pieces

of work done in this period of the mid to late 80s that were, due to the

state power, sort of dark and conspiratorial and reflecting the acute

paranoia of the late Cold War. I was very involved in doing different sorts

of work then, but one of the things I did at the time was a book called

Spycatcher [available at Amazon.com here], which at that time caused a lot

of stir because it got banned by the British government. It was a kind of

book about spies and I actually wrote it with a guy who was inside our MI-5,

which is like our version of the FBI sort of CIA type of thing. It was

really an expose of what was going on. At the time that that came out, there

was a kind of fantastic prolonged twelve month period where it was a court

case and it became a great set piece encounter conflict, really trying

to define where the boundaries lay between the government's desire to

protect national security and our right as citizens to know what is done in

our name.

The whole Spycatcher affair became a great controversy over here. At the

time there was a lot of work done that reflected that kind of paranoia.

There was a lot of drama done, there were films done, Spycatcher and

Watchmen. They were often linked together in the press, the zeitgeist was

paranoia. That's really where I come to Watchmen. That is why I am convinced

I can make the film, because I understood from personal experience the

milieu that gave rise to Watchmen. I understood a lot of the references that

Alan Moore used. He just happened to be expressing that paranoia in the

medium of the graphic novel, the comic book, where I and others were working

in different mediums. But we were all part of reflecting the same mood.

Q: So that means you're not going to be shying away from the political edge.

Greengrass:

No, not at all. I think it's very, very important. One of the

things that distinguishes Watchmen is that it's about the way we live today.

At that time it was about the way that we lived then. I think that we need

to make a film of Watchmen that reflects the times we live in. What's

interesting to me is that Watchmen, when it came out, reflected late Cold

War paranoia, and what was really interesting about it is that it was an

incredibly bold kind of allusive, allegorical, dense, rich story that

involved the collision of two elements: a real world running towards

Armageddon which is something at that time we thought was liable to

happen, with the great arms race of the 1980s so you have at the back of

Watchmen this ticking clock, which is these footsteps to Armageddon, which

is really a Cold War formulation. The Soviet Union invades Aghanistan

Q: And they move the clock ahead one minute. The nuclear clock.

Greengrass:

Exactly. And yoked together with that was this murder mystery

involving generations of caped crusaders. It was the collision of those two

elements that created the really great originality of Watchmen. What's

interesting today is that we live with new paranoias, but they are

paranoias. We are once again in very paranoid times, in a way that we

haven't been I think I'm talking about the post-9/11 world we have been

in levels of paranoia that we last experienced at the time of Watchmen.

Q: That's interesting because at the end of the 90s Watchmen seemed like it

might be a relic from another time. But like you said, 9/11 made it relevant

again. But on the other hand many people have said that they think 9/11

makes the movie impossible to make because of the way the novel ends.

Greengrass:

I don't agree. I think it's completely possible, and here's the

reason why: I think paranoia is driven by the circumstances of the world. In

the mid to late 80s, particularly young people at that time, of which I was

one, felt that the world was spiraling out of control. That there was going

to be a sequence, a dance, a series of footsteps that were going to walk off

over the edge into some cataclysmic event. The structures of the world were

designed were so intractable, were so locked in a sequence that we

couldn't escape that. I think that today a lot of people feel the same

thing.

Now it's not going to be the Cold War prism. The world is no longer a

bi-polar world divided between the USA and the USSR. We live in a unipolar

world. But the dangers, the nuclear dangers today, are profound and very

real. They're to do with nuclear proliferation, the spread of these weapons.

How do we deal with a world where these technologies spread? How do we keep

the peace? That's what drives us. We fear Al Qaeda, we fear terrorists, but

I think underneath that is a much deeper fear. It's a fear that, in a way,

the bi-polar world offered us curiously some security, where now we feel

that these weapons are spread, that creates challenges. How do we keep peace

in a world where these technologies are spreading? That's what I think we

have to use Watchmen to address. I think it's really important.

And I think that what it means is and we're engaged in a debate at the

moment in this production on how to do it you have to take the chronology

of Watchmen, and by chronology I mean what I call the "footsteps to

Armageddon" part of the machinery of Watchmen. You've got these two pieces

of machinery, the first of which is the murder mystery with the caped

crusaders and the various generations thereof, and the other is the

footsteps of Armageddon. What you have to do is take that chronology as it's

given to us in Watchmen and try to update it. You don't replace it, you just

say "What would have happened if that chronology continued?" One of the most

exciting things that I remember distinctly when I read Watchmen when it came

out was this idea of a world that was our world but that had taken a

slightly different course. Nixon had served three or four terms. Woodward

and Bernstein had been assassinated. G Gordon Liddy had become the trusted

advisor to the president. It was a kind of world turned on its head. What we

have to do is imagine what would have happened to that Watchmen world if it

had continued, rather than say let's start with a new paradigm. It's about

building on what's there in the spirit of the novel. That's what we're going

to try to achieve. So you feel that it's addressing our world, but you're

not losing the world Watchmen gave us. Which is the Nixon four terms world.

Q: Concretely speaking, is Nixon going to be president in this? Or would it be Bush Sr still in charge?

Greengrass:

I think you can't assume that Nixon would have served twelve

terms! You need to push it beyond there. We're not at the stage yet of

having decided that, but the methodology is clear. You've got to build on

that scenario and develop it. One of the interesting things about the

projects is reading the threads online. Seeing what the Watchmen community

feel and revere. What's important to them.

Q: You just launched a message board on the Watchmen site, right? [Check out those boards here]

Greengrass:

Absolutely. Last night, I think.

Q: The Watchmen fans can be very vocal. Are you going to pay attention to

what they're saying or do you have to ignore them to follow your own vision?

Greengrass:

It's very important to listen, hence this being a very important

dialogue to begin with. The reason for that is this: We're trying to make a

film. It's got to carry a broad audience. It's got to take Watchmen in a

sense back into the world again. But we have to carry with us the Watchmen

community that has loved and found depth and to whom Watchmen has spoken for

all these years. When you make any movie you have to ask yourself hard

questions, because you're going to be eating, eating, breathing, living and

sleeping the thing for the best part of two years. You have to ask yourself

some hard questions about what's bringing you to the project, what you can

give, in a sense. One of the things I said very early on to Larry and Lloyd,

who are producing, is that trying to carry the Watchmen community is very

like problems I faced in a very different area in various films that I have

made. In particular I made a number of films in Ireland, about the troubles.

One called Bloody Sunday and one that I wrote and produced but didn't direct

Pete Travis directed, very wonderfully Omagh, which was the terrible

bomb that killed many, many people in the small community in Omagh.

In both those films - in many ways I made them as bookends to a 30 year

conflict that, prior to 9/11, was probably the most important thing if you

were either British or Irish; it was central to your experience of the last

thirty years. Bloody Sunday was an event that really propelled the North of

Ireland into conflict. Omagh, thirty years later, really marked the moment

when the conflict became untenable. I wanted those two films to bookend this

tremendous tragedy. Both of them involved different communities in Northern

Ireland. One, the city of Derry for Bloody Sunday and the city of Omagh. In

both those films, terrible tragedies had engulfed those communities.

Different tragedies in Bloody Sunday the shooting of innocent people by

the British Army and in Omagh the killing of innocent people by a Republican

breakaway group. In both those films the communities felt that they

understood the story; they had a vested interest, they had a huge interest

in the making of the film.

Q: You actually had some survivors and witnesses of Bloody Sunday in that film, right?

Greengrass:

Correct. And for me it was central to making those films.

Absolutely central that as a filmmaker and as a production we built bridges

to the people who felt they owned that story. In the telling of it we sought

to carry them. That's not to say that the films that I produced reflected

every jot and comma and nuance as they saw it. You're making a film and

you've got to speak to an audience beyond. But I always saw it as absolutely

critical to both those films, the success of both those films, the integrity

of both those films that we carried the communities that had lived through

those events. It was profoundly at the heart of everything I did. I can't

speak to the quality of those two films, it's for others to judge, but one

thing I do believe is that those communities felt that those films reflected

their struggle, reflected their understanding of what had happened. And they

felt they owned them. Yet in a way those films also spoke to them and showed

them new ways of looking at these terrible events.

In a funny way when I looked at making a film of Watchmen, I felt that the

problem was analogous. Here you have a community a much bigger community

who feel they have a stake, in a sense, in this film before you even start.

Because of the love they have for the graphic novel, for the fact that they

feel very strongly, I suspect, about the integrity and authenticity in the

making of this. I think it's absolutely part of our purpose that we strive

very, very hard to carry that community with us on our journey. You begin

that by entering into dialogue with that community. By trying to understand

what Watchmen means to them. What it meant to them when it came out, what it

means to them today. To understand what they may feel are the opportunities

for the film and conversely what are the pitfalls for the film. You have to

listen, you have to understand, you have to engage in dialogue.

Of course in making a film you have to go on your own journey. You have to

expect judgement. But at the heart of this process is going to be that

dialogue. Will we succeed? I don't know. It's a journey. We're at the very

early stages. But what I want to convey is the seriousness of my purpose in

listening to people and engaging in dialogue, explaining how we're trying to

move forward.

Central to that is for me to explain to that community, "Hey, you know what?

I don't come to Watchmen in the way that maybe many of you do from a

lifetime of studying comic books and graphic novels. But I do come to it

having been involved in the zeitgeist that gave rise to Watchmen in my way.

I was doing my pieces at the time Alan Moore was doing his. I understand the

world very well, from a personal point of view, that gave rise to Watchmen."

That's really important to me, because that's what gives me the confidence

to take on this tricky and bold assignment.

Q: Are you going to be interacting with fans on the Watchmen message boards? You'll sign up and post?

Greengrass:

Absolutely. I can't tell you when, but I definitely over the

next few days make sure I make contact, and make sure I say to people that I

want to find ways of having dialogue. I want to come to events and meet

people. We have had a number of meeting on this film from the word go and

I mean from the word go. Paramount and Larry Gordon and Lloyd Levin, who

have been producing this picture, have been absolutely fantastic about

nurturing, supporting, filling with enthusiasm this concept. This is how

we're going to build this film, with dialogue at the heart. We may not

always agree you have to go on your own journey as a filmmaker, but you

have to try and carry people. The first stage is to try and understand. I

have to find forums where I can hear what people expect, fear and hope for,

and where I can explain what I'm trying to do and the solutions I'm trying

to get.

And hopefully it lives beyond the film, where that community can have the

experience together with the film. And one day the film becomes just part of

the Watchmen journey. It's one of those texts, those iconic texts. It's

going to live for a very long time.

Q: There are a lot of things that are tricky, especially getting across some

of the book's imagery. Take for instance Dr Manhattan his nudity is

important to his character, but how will you possibly get away with a

hundred foot tall naked blue man on screen? What thought have you put into

that?

Greengrass:

Some. Not all of our solutions are here yet. It's a matter of

getting the American football team through the door at the same time. What

is absolutely imperative is that we have Dr. Manhattan and that we dramatize

his powers and that we have a character who people that are familiar with

the comic book will recognize straightaway as Dr. Manhattan. We have to be

authentic to that vision. And we will be. Now if you're asking me is he

going to be stark buck naked from top to bottom from the first frame to the

last, actually in the graphic novel he's not either he has a rather natty

suit on some of the time.

Q: And in some of the flashbacks he has a superhero outfit on.

Greengrass:

Entirely. But what I don't think we will be doing will be a

little pair of jockey shorts. That's never been up to discussion.

In many ways the Dr. Manhattan of the graphic novel when I read that story

now, I find myself feeling that Alan Moore was many, many things but one of

the things he was is a prophet. There's an odd kind of a mismatch in the

graphic novel between the world where there is this great power underpinning

it called Dr. Manhattan and the bi-polar world. When you look today, we live

in a uni-polar world. In many ways we live more in Dr. Manhattan's era, I

think, then we did then.

Q: That's interesting. The Soviets in the book had no comparable Dr. Manhattan.

Greengrass:

This is my take on it, if you like. When the Wall came down in

1989, which was the event that I think more than anything else signaled an

abrupt change in the world as I had understood it in my life to the world

that we now live in. It was that collapse from a bi-polar world to a

uni-polar world, where there was only one great titanic power in the world,

and the rest of us whether you're British or German or Japanese or whatever

you are you are but pygmies to this colossal power in the world called

America. In many ways it's one of the things that makes me feel that

Watchmen speaks to us today in a way because the character of Dr Manhattan

that strange mixture of detachment and engagement, that loneliness if you

like, that inability to make the right move is very interesting when you

think about the world today. Ultimately Adrien's plan, vis a vis Manhattan,

is an interesting thing in the world today. Manhattan is a very key

character.

Q: Is Manhattan your favorite character? Do you have a favorite character?

Greengrass:

You know, I honestly don't. I think one of the main things that

makes Watchmen very special is that it's WatchMEN. It's not Spider-MAN. It's

not BatMAN. It's not SuperMAN. It's WatchMEN. It's this ensemble of

compelling characters with human depth and yet archetypal definition that

gives it that's' the genius, I think, of the piece. In a funny way I don't

have a favorite character, they're all magnificent characters. And they all

must have their moment in this film.

I suspect I know it will be through the next twelve months, right up to

the moment we lock this picture, it will be a large part of our business:

rendering the balance between those characters so you keep it balanced yet

when you're in a story you know why you're in it.

Q: That's interesting because I know that you're in the "getting the

football team through the door" phase, but are you giving thought to the

idea of how you're going to cast the picture in regards to giving every

character their moment? Are you looking for bigger names for some of the

roles, or are you looking for more of an ensemble?

Greengrass:

The honest truth is that we're trying to formulate a strategy at

the moment. There are a number of ways you can go with casting this film.

What's imperative is that you create balance, you create an ensemble. That's

the fundamental thing. But there are a lot of ways you can go. We are at the

stage of kind of looking at how that might work, and part of looking at how

they might work is analyzing how that community see it. It's very

interesting to me when you follow those [message board] threads, people have

suggestions and you say, "No I don't think that'll work," but you know there

are many suggestions that I think are fantastic. Of all the footballers not

yet come through the door, that's one that has not come through the door.

Q: Has the footballer come through the door that has led you to decide how

old to cast? In the novel most of the main characters are in their 30s and

40s, plus there are even older parents. Are you going to cast in that age

group or do you want to skew younger to grab a younger audience?

Greengrass:

I think that we will be not far off. I think that what's

absolutely essential in telling the story of Watchmen that you protect as it

were the three generations. I say that loosely, I don't mean it literally.

But it does seem to me that there is the group of characters in the

Minutemen, who rose and fell. Within that group you have Sally and the

Comedian. Then you have really three characters who emerge at a later stage:

Rorschach, Manhattan and Adrian. And then you have Dan and Laurie who are a

bit younger, almost children of the Minutemen. They are a little younger

again than Rorschach, Manhattan and Adrian. That's the thing we need to

preserve in our casting, that understanding you have of the relationship

between those three generations they're not strictly generations, but I

think you see what I'm talking about.

Q: The novel is so dense. There's no way that you could, within a two hour

movie, get every element of that world across. What are the elements of the

Watchmen world that you want to get across?

Greengrass:

I'm not sure that I agree with the first part. I don't think you

can fully reflect every single last detail, you're right about that. But a

film works in a different way, I think, to the plates of a graphic novel. In

its way I think you can suggest depth of a different kind. I absolutely do

want, intend and believe that we will bring to screen a Watchmen world that

has depth and allusiveness. That it has that kind of richness and texture of

the graphic novel.

What I think is very, very important is that the world be real. That it be

the world that we understand is the world we're living in, rather than it

being a kind of romanticized Gotham City. I think a second thing that's

important is that the world unfolds in a manner consistent with our world

outside. When the novel came out that whole view of the world where Nixon

got elected again and again, Woodward and Bernstein got assassinated, G

Gordon Liddy was a trusted advisor in the White House that was a brilliant

conceit. It was not the world we lived in but it was the world we might have

lived in. A fact that we must and will get across in this film.

I think the second thing that's really important is that when you sit inside

that world our ensemble of caped crusaders, that you understand that these

are human characters, flawed characters. That they're not superheroes or

that only one of them technically really is, Manhattan. It's that concept

that you have a human drama that involves this cast of characters and that

you understand where they've come from. That this is not just some casual

thing that they do, they do it because they're compelled.

There's something about it, in an odd way, that reminds me of One Flew Over

The Cuckoo's Nest, both the novel and the film. You're looking at a world

that is of our world, but yet is very separate. You look at Diane Arbus'

photographs and you have something of the same quality. I think that therein

lies where we need to go with Watchmen as a piece of drama.

Q: I think that there are three elements of the novel, and you've hit on two

so far. There's the upfront story element, which is the murder mystery. Then

there's the political aspect. But the third element is that the novel serves

as a deconstruction and critique of superheroes and comic books. Will you be

delving into that?

Greengrass:

Yes, we absolutely will do, and you are absolutely right, that's

the third element. I think it's important that we do it and that our

audience, particularly the Watchmen community, know that it's being done and

enjoy that it's being done and that it's done on a sophisticated level.

There you have, in the graphic novel, where the real depth and texture in

it, there's a limit to how much we can do. But I think that we will do

enough to keep all three of these elements in play together, working

together in appropriate balance.

When you said the political element, I always call it the footsteps to

Armageddon. Because I think that element is actually incredibly exciting. I

say that because as we've come together over the last few weeks I've asked

my team to watch a BBC drama made at about the time that Watchmen came out

called Threads. It was one of those unique events you can only have in a

country like Britain on television, where everybody tunes in to watch the

same thing at the same time. Threads was a dramatization of what would

happen if there was a nuclear conflict in Britain now. And I'm talking

1986ish when it came out.

It was responding absolutely head on to the same sort of paranoia that begat

Watchmen. But it did it not in comic book form, but in straightforward

imagine that in '61, '62 it was the Cuban Missile Crisis, but in the mid to

late 80s what would be scenario that got them to the Missile Crisis and then

let's imagine that they couldn't get out of it. I hadn't seen it in 20

years. I remember it as one of those seminal audience moments in my life of

watching something where I was horrified, compelled, just could not lift my

eyes from the screen. I was watching something that was speaking to me about

what was happening in the world. It was actually a very beautiful screenplay

about a young couple in Sheffield, moving into their first apartment

together. It was full of youthful hope. I think she was pregnant. It was set

against this gathering international crisis that nobody took any notice of

until these individual dramas got blown apart by this terrible cataclysm.

A lot of it was told in bits of news footage and newspapers. Told in the

exact same way that Alan Moore tells it in Watchmen. It's just at the heart

of his story is this caped crusader murder mystery and at the heart of

Threads is this small domestic kitchen sink love story. When I started

Watchmen a couple of months ago One Flew Over the Cuckoos Nest was in my

mind and so was Threads. I watched it and of course the special effects now

it was a small television film and there were no computer special effects.

That bit didn't work. But the first forty-five minutes I found spoke to me

today just as they had done two decades ago. Showing the way the world can

turn can be utterly compelling, and ask you questions. That why I believe

passionately that we can make this thing work in two hours because we will

have a piece that will speak to our fears. And also show us some ways to

deal with our fears. In some places in Watchmen that's there too.

Q: Alan Moore has been very vocal about not being happy with the movie

adaptations of his work. Have you spoken to him about this, or tried to

speak to him, or even just hope to speak to him?

Greengrass:

I hope to, I would love to. I intend to try. In many ways he's

made his position plain about the films. They're not my films. I wasn't

there. I wasn't at the scene of those accidents. All I can speak to is

where I come from, where I come to Watchmen from and what I would like to

do. I couldn't presume to tell Alan Moore it's going to be great. It's

exactly the same thing as when I sat down with families who lost loved ones

in the bombing at Omagh or who lost loved ones in Bloody Sunday. In the end

you can't say to people like that, "Listen, I'm going to make this film and

it's going to be great!" You can't say that. All you can say is, "I would

like you to give me the chance to show you what I have done and you judge me

on that." That's all you can ask. You can ask to be judged on what you tried

to do. You can't ask for endorsement in advance, it seems to me. You have to

earn respect with what you do.

That is the same with the Watchmen community. A lot of people out there will

be sceptical about us, will doubt that it can be done, will worry about how

we will do it. All I can say in all honesty and humility is, I understand

that. I believe with a passion that we can do it, I believe with a passion

that I was making a contribution in my country as Alan Moore was in his way

at that time, but I was dealing with a lot of the same material and ideas

at that time. I beg only that you judge me when I'm done, as I'm sure I will

be.

** IN THE PIPELINE **

** IN THE PIPELINE **